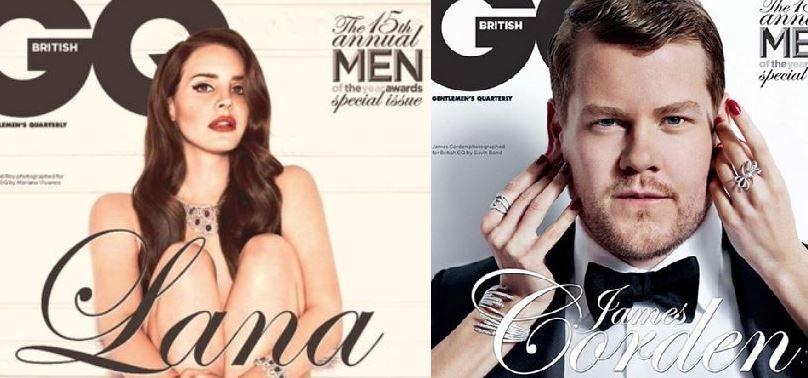

It's common knowledge that in pop culture, women are often treated as sex objects, and men are not. Last week, this message was reiterated to grand effect when the Facebook group "Object! Women Are Not Sex Objects" put together the alternate covers for British GQ's "Man/Woman of the Year" from 2012. As you can see, one of these things is not like the other . . .

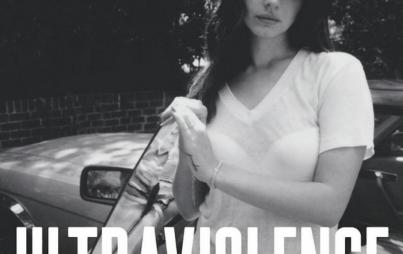

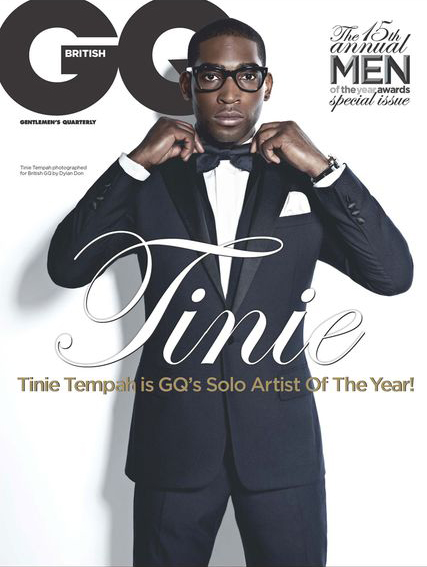

Lana Del Rey, the only woman selected, appears nude except for some jewelry. The men selected—Tinie Tempah, Robbie Williams, John Slattery and James Corden—all get to wear clothes. As Lindy West wrote at Jezebel, "I don't have a problem with a naked lady here and there per se, but when ALL YOUR LADIES ARE NAKED, those of us ladies with clothes on start to wonder why you even keep us around."

West also notes, "Objectification is complicated"—which is why it seems worth returning to these covers, even a couple years out. (It also seems pertinent considering that this year's Woman of the Year, Kim Kardashian, was similarly nude and come-hither.)

Yes, it's certainly true that Del Rey is objectified. But is her objectification what makes her cover different than the others? Or, to put it another way, is she the only one who is being objectified on those covers?

I don't think she is. Look at this image of James Corden, for example:

There he is in his suit and tie, looking earnest and perhaps slightly amused, as various women's hands stroke his face and pull aside his suit jacket. It's certainly a fantasy for guys, since it imagines multiple women fussing over a man. But it's also an image that presents Corden as a sexual object—something to stroke and toy with and fondle.

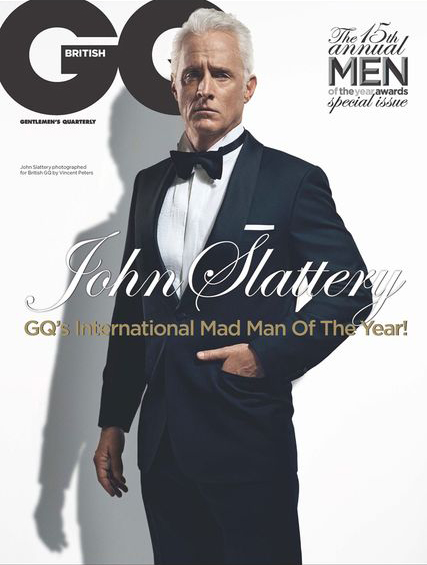

Or look at John Slattery's cover:

The hand in the pocket at waist level draws attention to a certain concealed-but-highlighted anatomical part. Slattery's not naked, but the picture is still (not that) subtly telling you that it's about his virility and manliness. Sex is not absent from the image.

What's different, then, isn't objectification per se—both men and women on these covers are sexual objects. But the method of objectification is linked to gender. Del Rey is seen as sexy because she is vulnerable and accessible. This is emphasized not just by her nudity, but by her body language: She's pulled into a ball, her adult jewelry contrasting with the implied little girl shyness.

The fact that she's nude perhaps even distracts from the key difference between the images. Del Rey is seated, cramped, passive; one eye is slightly and demurely obscured by her hair. Tinie Tempah, on the other hand, stands legs apart, arms spread, his eyes looking directly at the camera (all the other men share similarly direct poses):

Del Rey is a shrinking, uncovered, waiting sexual object. The men are covered, self-confident, bold, thrusting sexual objects. For Del Rey, the sexual objectification is derived from the disempowerment; for men, it's derived from the empowerment.

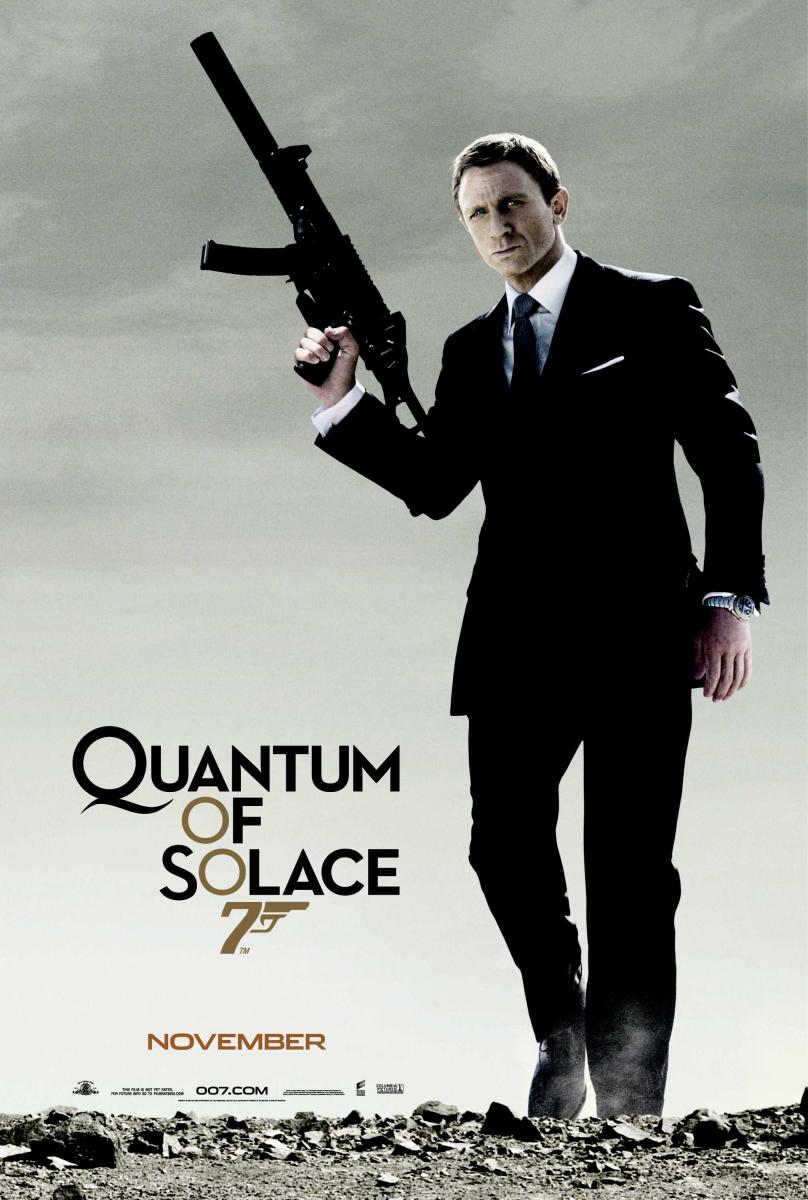

That's not only the case on the GQ covers. Men are often sexualized by being covered, self-contained and in control, rather than exposed and available as women are.

Here's Daniel Craig, for example, with suit, tie and phallic symbol, in the poster for Quantum of Solace:

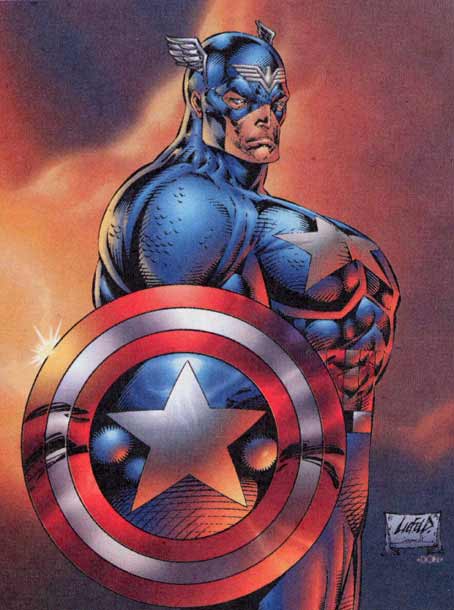

And here's an infamous drawng by Rob Liefeld of a grotesquely, anatomically improbable Captain America.

Cap here is definitively fetishized; his bulging chest seems like a (confused) straining penis substitute in itself. But he's also almost entirely covered, in skin-tight spandex and a mask. The costume emphasizes his mastery and self-containment without concealing the awesome musculature of doom. The clothing doesn't save him from objectification; it's part of the objectification.

Liefeld is easy to mock, but the general iconography—fully clothed, upright, staring out defiantly at the viewer—is hardly unique (see here, here and here for just a few more of many examples). It's also the exact iconography used by GQ on its covers—and, interestingly, is similar to imagery Del Rey plays with, much more thoughtfully, in her own videos.

In " Shades of Cool," for example, Del Rey, wearing a swimsuit, pulls herself dripping from a pool; cadaverous tattoo artist Mark Mahoney, fully clothed, stares at her intensely. As she stares back at him, she sings "I can't break through your world."

Mahoney's clothing becomes a symbol of his romantic, painful inviolability. The video also repeatedly shows close-ups of Mahoney's eyes; his gaze is a fetishized totem, a look to be looked at. Del Rey in the video doesn't exactly undermine gendered tropes; she's still in a swimsuit, he's still in clothes. But she does seems to be playing with the idea of herself, as object, also being an objectifier—which raises the question of who is really active and who is really passive. If the looker's look is being objectified, is the object of the look really passive? Or is power just a costume, donned for the sexual appreciation of the woman being looked at?

Del Rey's video is hardly a call for gender revolution, but at least it suggests that she, and the video's creators, put some thought into the iconography they're using. That's not the case for the GQ covers, which blandly use the default signifiers for male and female sexiness. Men are active and powerful, women are open and vulnerable, repeat.

The covers reinforce gender stereotypes not because they present only women as sexy, but because their ideas of what sexy can mean—for men and for women—are so constricted.